The War on Drugs and International Development

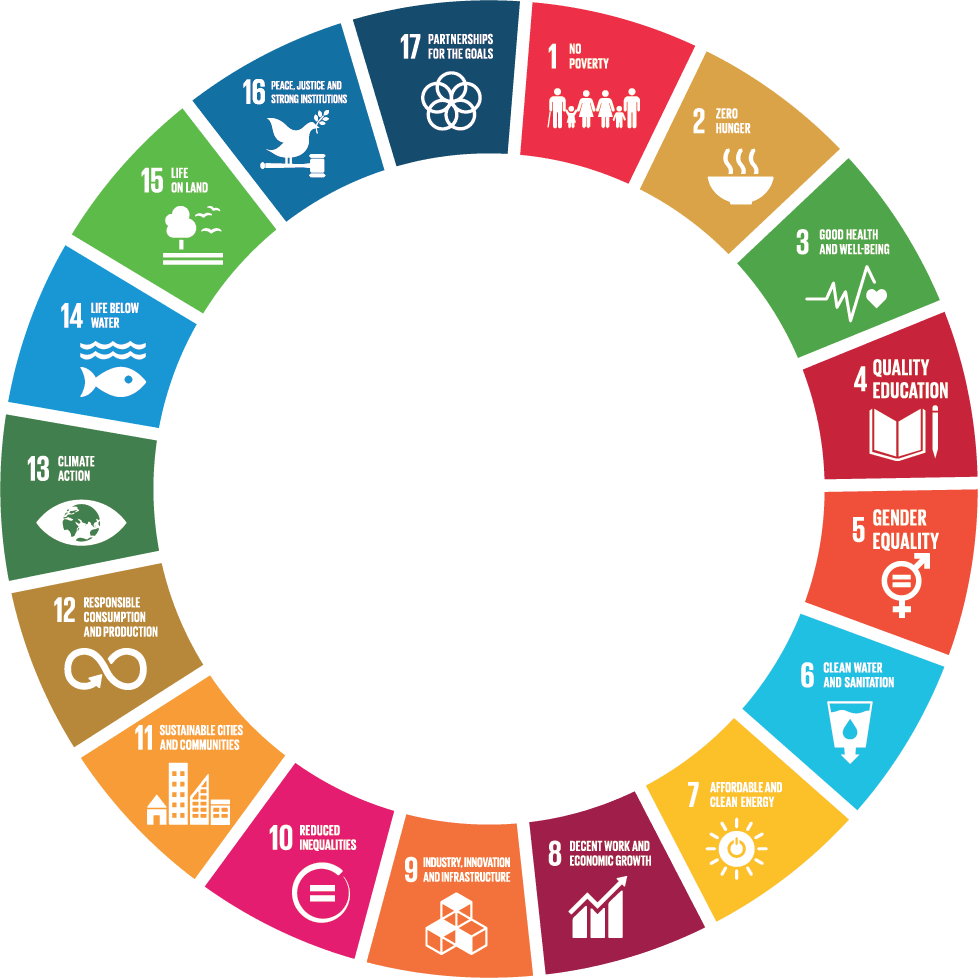

In September 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by world leaders and came into force on 1 January 2016.

Aiming to build on successes achieved by the Millennium Development Goals, the SDGs will shape the mainstream development agenda for the next 15 years. In this context, it is essential that the global response to drug use, production and supply aligns with, and contributes to, the SDGs – and that the development community pays greater attention to the role of drug policy in this agenda.

The current approach to global drug policy, dominated by strict prohibition and the criminalisation of drug cultivation, production, trade, possession and use, has not only failed in its objectives: it is also undermining efforts to tackle poverty, improve access to health, protect the environment, reduce violence, and uphold the human rights of some of the most marginalised communities worldwide. The upcoming UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on drugs on 19-21 April will provide a rare opportunity to bring nations together to genuinely try and find a solution to the problems caused by the war on drugs.

First, some of the ways in which drug control efforts have impacted on development must be analysed, before discussing how global policy can be modified to generate a more positive impact in developing nations.

The key issue is the failure of current policies to address the socio-economic root causes of the so-called “world drug problem”, in many cases exacerbating them. This encompasses poverty, inequality, discrimination and social and cultural marginalisation, as well as the stability of countries.

Crop eradication and alternative development programmes, particularly those involving eradication as a conditionality, have extensive negative impacts for crop producing communities. The destruction of what is often the only cash generating crop grown by farmers further alienates them from the state by removing their sole source of income. Indeed, in Afghanistan it was noted that the program of crop eradication became a highly effective recruitment tool for the Taliban. Crop eradication, then, deepens regional poverty and food insecurity and often leads to farmers being displaced from their homes.

Negative health impacts can also be clearly seen during these programmes, with one of the chemical herbicides utilised in Colombia being designated by the World Health Organisation as a carcinogen. Environmental impacts also occur, with damage to the land and water sources that communities rely on to survive, alongside general destruction of biodiversity and environmental degradation. The so called ‘balloon effect’, in which production moves to new areas after crop eradication, also causes deforestation through the expansion of agricultural frontiers.

International drug control conventions are also enforced overly strictly. The intention to prevent the diversion of controlled medicines to illicit markets is well meaning, however it results in significant constraints on access to essential medicines, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The inability to access, for example, pain relieving opiates critically hampers the development of good healthcare in developing countries, lowering life expectancy and stunting economic growth.

Heavy handed and militarised efforts by states to control the illicit drug trade fuels insecurity and conflict. Criminal competition over control of the illicit trade is often violent, with significant impacts on homicide rates and other forms of insecurity, and state responses often only fuel the cycle of violence. This is evidenced in the upsurge of drug related violence in Brazil’s favelas whenever military forces move in, compared to the pacifying police units that take a community focused approach. A further issue is the drug trade being used by armed groups as a major source of finance, such as with FARC in Columbia.

The vast profits from the illicit drug market lead to the corruption or collusion of security services, judiciaries, politicians and even whole electoral processes. This undermines people-focused security and justice service provision, as well as the effectiveness and accountability of institutions of governance. This not only hampers development, but also can drive state fragility and increase conflict risks in the long-term. This is highlighted by allegations by drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s daughter, Rosa Isela Gusmán Ortiz, that he bankrolled senior politicians’ campaigns in return for support in avoiding US patrols.

On an individual scale, the absence of harm-reduction services leads to negative health impacts. This includes preventable HIV and hepatitis infections that are associated with injecting drug use, as well as preventable overdose deaths. There have been moves to try and counter this, with needle exchange programmes and the opening of medically supervised injection centres in a number of countries. Even where these services do exist, however, the criminalisation of people who use drugs acts as a significant barrier for people attempting to access health care, preventing them from seeking help for their issues and pushing them into the margins of society. The overall negative impacts of drug control policies, particularly disproportionately large sentences and crop eradication, disproportionately affect women, who are most commonly engaged in drug markets at a very low level.

It is crucial that the UNGASS on drugs addresses the fundamental connections between drug policy and sustainable development, outlined above. A failure to do so risks many more years of an unproductive, wasteful war on drugs that harms many more than it helps. The following suggestions go some way to providing a future drug policy that positively contributes to peace and development, as part of achievement of the SDGs.

Initially, it must be agreed at the summit to welcome the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and noted that drug control policies must not undermine the achievement of the SDGs. In this vein, the current drug war paradigm must be acknowledged as a major obstacle to achieving many of the SDGs, an in light of this all alternative policy options should be tabled to fully consider how these might better facilitate the achievement of the SDGs.

The SDGs should be made a central consideration in the development and implementation of all drug control measures. This should involve dismantling initiatives which negatively impact on development and prioritising those that contribute to improved sustainable economic development, secure livelihoods, food security, strengthening of local institutions, improving infrastructure, access to markets and gender equality. This would form a drug policy that was ‘development sensitive’, actively engaging local communities in meaningful consultation and participation in national development policies and action plans.

An expert panel should be established to conduct a thorough and regular review of areas where drug policy is positively or negatively impacting progress to achieve the SDGs. This panel should also propose concrete measures to increase coherence between drug policy and development mechanisms within the UN system, including increased oversight for relevant UN agencies working on development. Old metrics and indicators in the sphere of drug policy should be overhauled and replaced with ones that are aligned with the SDGs. Development of new guidelines which reflect the socio-economic foundations of involvement in the drugs trade.

In line with efforts to meet SDG 15, relating to life on land, the environmental consequences of forced crop eradication must be addressed. This includes ending the practice of moving illicit crop cultivation into areas of ecological importance to evade the eradication campaigns. SDG 16, “peace, justice and strong institutions”, necessitates active measures being taken to reduce heavy handed and militarised responses to the violence associated with drug trafficking. In their stead, creative policy solutions should be developed and implemented to reduce the levels of violence.

Access to controlled medicines must be ensured to achieve SDG 3, particularly in developing countries. This should be done through national legislative and regulatory frameworks that prioritise access to essential medicines. Furthermore, the provision of harm reduction and evidence based drug treatment, and HIV prevention, care and treatment must be recognised as core obligations of Member States under the right to health, and these efforts must be scaled up from their present level.

Alternative measures to conviction or punishment for drug related offenses of a minor or non-violent nature should be developed and adopted. This follows into supporting decriminalisation and alternatives to incarcerations for people who use drugs, as well as small scale producers. Disproportionate sentences for drug offenses must also be tackled, focusing particularly on the needs of women and other marginalised groups. This supports SDGs 5 and 10, relating to reducing inequality and supporting gender equality.

By bringing global drug policy in line with the new, internationally agreed, SDGs, the UNGASS would show commitment to improving the lives of countless people currently affected by the war on drugs. The mistakes that have been made since the war began should not be repeated, and the upcoming special session provides a rare opportunity to change the course of global policy in a real, meaningful way. The UN website states “for the goals to be reached, everyone needs to do their part” – it remains to be seen if they take their own guidance.